With all the negative news the last few days, I thought it would be good to share something positive. A “feel good” post if you will. So today we are going to explore some of the positive aspects of National Socialism.

My work flow is such that it takes several days to prepare a post and podcast episode. Because of this, current events may or may not be all that current by the time this gets posted. I mention this because what follows was not what I was originally was going to post.

As I was focusing on putting the finishing touches on the December edition of The White Worker, and having little time for anything else, I had thought I would do the “two birds with one stone” thing and post here one of the articles which is in the aforementioned upcoming issue. Specifically, each issue of The White Worker this year has included an article debunking some aspect of the standard Holocaust mythology. The essay I planned to post pulled all these individual articles together in a sort of summary and conclusion format, and examined why the Holocaust narrative continues to be told even though it is becoming increasingly apparent that a great deal of what is accepted as “fact” is nothing of the sort— as illustrated by the articles under discussion in The White Worker.

Then this last weekend happened: shootings, stabbings…etc. In short, Jews in the news everywhere and a generally a violent, negative news cycle at that. It’s what I would have called “bad vibes” in my younger days.

Frankly, with Christmas just around the corner and this ostensibly being a time for thanks and reflection, I felt it would be “piling on” the negatives. That isn’t what I want to do and it isn’t how I want to feel. With 2025 coming to close (none to soon), I want to begin to end it on a positive note.

So, instead, for this penultimate post and in honor of the Christmas spirit, I decided to toss everything I had planned and go in a completely different direction. Because of this, I hope you will forgive me if this is a little more “off the cuff” than usual.

It is easy to focus on the negatives; doing so has become the defacto methodology of political discourse in this country going back to at least the time Karl Rove helped Shrub, Jr. get elected in 2000. We no longer hear of visions and aspirations, worldviews and destiny. I am guilty of this too: many of my posts focus on what is wrong with this country, that policy, or specific individuals in the news. But I do try to temper that negativity as often as possible with some alternative vision, some answer, some glimpse into the better world National Socialism would create. It is not enough simply to complain: we must offer solutions and alternatives.

There is method to this madness. First, political and economic systems strive to self-perpetuate. By this I mean, the entrenched forces in any given society actively work to grow and maintain their power and influence, often by denigrating other systems and choices, often by not allowing any choices at all. Because of this tendency, National Socialism as a viable alternative to the status quo is never going to get an honest airing in political discourse. This wasn’t always the case: as late as 1951, even after years of “de-nazification”, the Federal Republic of Germany conducted a survey and found that nearly half of its citizens described the period between 1933 (when Adolf Hitler became Chancellor) and 1939 (when the war started) as the one in which things had gone best for Germany. Not the Weimar era, and not post-war Germany.

All “politics” aside, for a large part of the population, the image of National Socialism was characterized not by the negative stereotypes perpetuated during the war by the Allies, and after the war by everyone else, but by a reduction of unemployment, an economic boom, tranquility, and order. The facts, which people at the time could well remember, countered the standard narrative lies told by the existing power structure.

The second reason to highlight the real positive nature of National Socialism now is one of record. Good news: nearly 50% of all “Holocaust survivors” will pass away within the next six years, while 70% will die within 10 years and 90% within 15 years. The bad news is that these numbers also apply to ethnic Germans who have first-hand knowledge of daily life in a National Socialist state. A new generation, the post-war generation, must carry the torch forward.

To that end, I thought it would be good to write a positive, affirmative post that touches on some of the highlights and benefits experienced in life lived under National Socialism, and from this, to learn what a person might expect under such a system. Of course, to do this, we must look at the only National Socialist state in history: National Socialist Germany.

To get started, I think it is important to remember two points. First, while every effort was made to create a National Socialist state from 1933 to 1945, this time frame can be (and should be, in my opinion) divided into two periods: pre-war, and war. The pre-war period is characterized by a real attempt to re-shape an existing society along National Socialist lines. The war period is characterized by a struggle for survival and necessary measures of expediency. As Jewish historian David Shoenbaum writes (because, for some reason, Jews simply love to write about the Third Reich), “War by its nature accelerates social change. Wartime society is both more egalitarian and more mobile than society in peacetime. Its goal and priorities are set by the war itself…Goals and decisions are no longer free in even the relative sense they are when the nation is at peace. From September 1939 on, the initiative in German decision-making gradually left German hands.” [Hitler’s Social Revolution, 1966].

The two periods in question required different means and methods. When people point to the “failure” of National Socialism, they often focus on decisions and actions taken during the war years. To truly understand what National Socialist Germany hoped to achieve, it is necessary to look, instead, at that time period before the war when attention and resources could be focused on the task at hand (remaking society) and not merely survival. It is worthwhile to remember that if National Socialist Germany had to suspend or repurpose certain aspects of its ideological goals, so too did the Allies with their rationing of sugar and gasoline, their suspension of typewriter and automobile production, and their drafting of men into the military and the subsequent change in the labor force moving women into the armed forces and factories. In short, the war effort comes first for any combatant.

Second, National Socialism was an answer to a myriad of problems, some of which you may recognize: Germany was late to the international game, as German unification did not transpire until 1871; there was a vast disparity between the haves (landed gentry, money-lenders, and foreign investors) and have-nots; high unemployment (estimates run between 5 and 7 million pe0ple); an economic depression, which, while worldwide, struck Germany particularly hard in a large part due to reparations and the French occupation of the their industrial sector, the Ruhr Valley; and a grossly unreasonable “peace” treaty whose real aim was victor’s justice and a desire to forestall national pride by laying the cause of the First World War solely at Germany’s feet.

In addition, The Weimar Republic became the destination for hundreds of thousands of refugees who escaped the aftermath of the Russian Revolution in October of 1917, the subsequent civil war and the implementation of the Soviet system. The same fate was shared by tens of thousands of Eastern European Jews who were looking for protection from pogroms and anti-Semitic developments in many parts of Eastern Central, South Eastern and Eastern Europe. The government in Weimar, really a pseudo-Republic largely beholden to outside interests and communist manipulation through the KPD (Communist Party of Germany, which at its height in 1932 held 100 seats in the Reichstag and took its marching orders from Moscow), proved incapable of dealing with the problems. Because of all this, and for other reasons still, Germany was ripe for an alternative and there were three main choices: The existent, ostensibly Democratic system controlled primarily by foreign money and non-German interests, Soviet communism, or National Socialism.

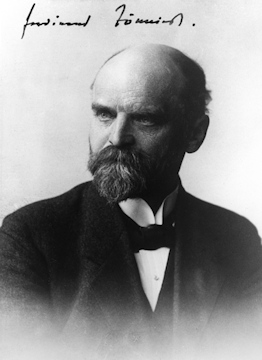

What did National Socialism have to offer? In short, it promised a society which, while recognizing differences between persons, valued the larger commonality of its people as an ethnic group or race, regardless of class or education. It is interesting to note that National Socialist Germany and is promise of Volksgemeinschaft (the ethnic community) was built on much firmer foundations than people generally give it credit for. It was not something the NSDAP created from whole cloth. The ideas that would become National Socialism had been floating around in Germany for some time. For example, in 1887, Ferdinand Tönnies, a German sociologist, economist, and philosopher, published Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft [Community and Society] in reaction to the growing tensions between traditional lifestyles and the emergence of industrialized society that was overtaking not only Germany, but the rest of the world. Gemeinschaft (community) represented traditional values, personal in nature, being organized around a sense of moral obligation to one another. Small rural towns typified the Gemeinschaft, where tight-knit, and exclusive, groups shared connections through kinship, common language, and beliefs. Three types of Gemeinschafts existed, according to Tönnies: Gemeinschaft by blood, Gemeinschaft of land, and Gemeinschaft of spirit, with the two former creating the latter.

Combined, these three types made, “a truly human community in its highest form.” You might also recognize the forerunner of Blut und Boden, blood and soil. Tönnies viewed Gemeinschaft as a “living organism in its own right;” such community could not be torn apart by distance. The Gemeinschaft linked people together through commonality: “Common goods—common evils; common friends—common enemies.”

After Hitler came to power, the leaders of the Third Reich would undertake serious reforms to ensure Germans felt the unity of their concept or version of Volksgemeinschaft- the German ethnic/racial community. This genuine effort on the part of the NSDAP ensured its continued popularity throughout the 1930s. Advances in science and the creation of an intricate social welfare system, along with a promise of even better things to come in the future, would demonstrate and make manifest to Germans their inclusion in the ethnic community like never before. All strata of the German population were to benefit.

Third Reich officials introduced several key policies to demonstrate to German citizens their ethnic belonging in the National Socialist state. Many of these early policies would come in the form of welfare initiatives—keep in mind the dire economic situation and unemployment numbers at the time. The National Socialist People’s Welfare Organization (NSV) offered monetary aid to impoverished German citizens, even providing subsidized healthcare. Likewise, the Winter Aid program set aside provisions like coal and food for poorer Germans in the winter months, which were traditionally tough times for many civilians. The expression, “A People Helps Itself,” became the common rallying cry for these initiatives. More affluent citizens were constantly urged to donate some of their earnings in order to fund the programs for the NSV, while top Nazis officials appeared with some regularity during public campaigns to solicit donations.

Similarly, all Germans, and even Party officials, participated in One Pot Sundays once a month to ensure working class citizens could find proper foodstuffs. Cooking in ‘one pot’ (ein Topf) was supposed to symbolize the National Socialist creation of ‘one people’ (ein Volk). The crafting of a delicious casserole by combining diverse ingredients was analogous to the uniting of the various native German peoples into a single and self-sustaining whole. One Pot Sundays demonstrated a form of collective discomfort or austerity for the betterment of the community by reinforcing the concept that all Germans were sacrificing larger and more enjoyable meals to ensure that all ethnic Germans had enough to eat.

Furthermore, those who did not partake in One Pot Sundays outed themselves as enemies of the community. Hitler expressed this sentiment in a 1935 speech when he declared,“You have never known hunger yourself or you would know what a burden hunger is…Whoever does not participate is a characterless parasite of the German people.”

Every year from October to March, volunteer groups moved across cities and towns requesting donations for the Winter Aid program. These initiatives achieved spectacular results. By 1939, the NSV had received 2.5 billion Reichsmarks in donations. In the same time frame, One Pot Sundays saved fifty million marks. NSV, Winter Aid, and One Pot Sundays all introduced Germans to collective suffering for the larger community. Collective sacrifice was essential for the Volksgemeinschaft. By giving up additional spending money, affluent Germans could financially uplift even the poorest citizens. This had the additional effect of quelling anti-German notions like consumerism, though participants of these initiatives could nonetheless expect rewards for their troubles: Germans received special pins recognizing them for their assistance in the welfare programs. These pins, along with several similar trinkets, became highly collectible items.

If the welfare initiatives in the early years of the Third Reich taught Germans to sacrifice for the collective good, other efforts in the construction of the Volksgemeinschaft were aimed at making life more enjoyable and rewarding.

It is important to know that in the first part of the 20th century, it was generally assumed by the elites in industrial nations that leisure activity was the purview of the well-heeled and detrimental to the work and productivity of the common masses. German National Socialism challenged this assumption. In November 1933, Robert Ley, head of the German Labor Front (the DAF), announced the formation of a new subsidiary organization: the Strength Through Joy program (Kraft durch Freude, or KdF). The KdF held as its mantra that work and leisure were not mutually exclusive concepts, but instead reinforced one another. We’ve looked at the KdF program on this blog before, so be sure to read that if you are interested in more specifics. But for our purposes, it is enough to know that the goal was to improve the leisure time and communal activities of ethnic German workers. National Socialist Germany believed, truly, that adequate work could not be achieved without adequate rest and relaxation. KdF granted all Germans regardless of social standing access to activities usually reserved for the wealthy.

Workers received paid vacation (something largely unheard of at the time), attended orchestral concerts in their own factories, participated in sports and group exercise, and other “after work” activities were subsidized so that even the poorest unskilled worker was able to sail or play tennis. Firms were given discounted block-bookings for the civic theaters at night so workers could attend; factory libraries were expanded; and folk-culture groups revived and performed traditional rural songs and dances.

However, the DAF (Deutsche Arbeitsfront, or German Labor Front) and the KdF program not only improved worker’s leisure activities. An equally important tenet of KdF was the improvement of working conditions. In a 1936 article titled, “Senseless Work is Un-German,” Karl Arnhold suggested, “The German working man must know and be convinced that there is a sense of purpose to whatever he does. He will always inevitably falter as soon as he realizes that there is no point to any task he has been assigned.” The urged German employers to create a sense of purpose in the workplace through better wages and competition. From this, Arnhold proposed that labor efficiency would rise. The Nazis undertook several initiatives that seemingly affirmed Arnhold’s declaration. German workers received new hours to allow time for their after-work activities. New factories replaced dilapidated industrial sites, while many others underwent complete refurbishment. The DAF and KdF employed millions of German citizens. KdF stressed egalitarianism by including not only working-class citizens, but employers, and white-collar employees as well.

The KdF program was generally held to be a success. In a 1935 report titled “On the Anniversary of the Establishment of Strength Through Joy,” Robert Ley touted some of the economic and social benefits KdF had provided Germany: 2.1 million Germans had partaken in the paid vacations offered by KdF through the Department of Travel and Hiking. Likewise, 80,000 “national comrades” participated in cruises that sailed them around Europe’s most beautiful landscapes.

Through all of their excursions, German citizens spent almost forty million Reichsmarks that directly fueled the Reich economy. Seven million additional Reichsmarks came from railroad tolls alone. But luxurious vacations across the continent paid off not merely monetarily, but ideologically as well, namely, by encouraging a sense of racial superiority among the travelers. Workers became convinced that National Socialism had created a matchless level of care unequalled anywhere else in the world for the working people of the Volk by observing the living conditions of other people. Ethnic Germans could recognize their superiority by noticing that not everyone lived as affluently as they did, and thus, perhaps that the Third Reich’s racial and social vision had real legitimacy. The tangible effects of the initiatives notwithstanding, KdF offered a first glimpse, however imperfect in its early stages, of Volksgemeinschaft in action.

Said one paper that examined life in National Socialist Germany and the effects of Volksgemeinschaft, “…There was a feeling that life had changed: during this period, a large majority of Germans really believed in a ‘national resurrection’ and in their chances of a personal career, a heroic future, and in a better life for themselves and future generations.”

As noted previously, social equality may have remained incomplete, but the “sheer forcefulness of social welfare and other reconstruction work strengthened the notion that national life could and would be remade.” One example of the tangible results and social mobility based on Volksgemeinschaft and rewards based on merit and not on social station is exemplified by the story of a WWI veteran and early NSDAP member named Martin Luther. He was a small businessman who eventually rose to the rank of Undersecretary of State in an “…unprecedented and mercurial career ascent for a man derided as the ‘former furniture remover’ by the old elites in the Weimar Foreign Office, the most aristocratic and traditional among the German ministries.” As another soldier stated, “We believed in a new community, free from class conflict, united in brotherhood under the self-chosen Führer, powerful . . . national and socialist.”

This is by no means a complete picture of life under National Socialism. Think of it as a small taster. There is much left unsaid to be explored later: education and the youth experience; small business growth and economic prosperity; law and order, etc. But it’s a start.

Finally, it is worth noting that a primary source used for this article was a thesis paper published just last year in May, 2024: Community Race and National Socialism_ The Evolution of the Ideal, by Robert B. Anderson at East Tennessee University. I find this very exciting, as it gives one hope that, in time, the truth about National Socialism will be more widely known. I consulted several sources for the content of this post, including books from my own collection and online sources, but Mr. Anderson’s paper was invaluable.

However, in fairness to the author, it should be mentioned that his work is in no way an endorsement of National Socialism or Nazi ideology. Instead, he tries, and I think succeeds, in demonstrating that the concept of Volksgemeinschaft and its implementation was more than simply a propaganda effort designed to bolster the Hitler regime, and was, instead, an honest effort to remake German society and a true reflection of the National Socialist worldview.

As the abstract for his thesis states:

“Historiography of the National Socialist Volksgemeinschaft, or people’s community, has traditionally been divided between historians surmising its construction under the Third Reich as a genuine undertaking meant to uplift German society, and those who view the project as a propaganda effort which assisted the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in retaining legitimacy. Utilizing the plethora of works written on the topic, and a handful of primary sources from pre-Nazified Germany, NSDAP officials, and average citizens alike, this work will demonstrate that, as early as 1807, German philosophers, statesmen, and eventually a large majority of the population yearned for the national unity of Volksgemeinschaft; that the National Socialists adapted the concept for their own ideology. Furthermore, this study finds that, although Adolf Hitler indeed exploited the Volksgemeinschaft for his retention of power, the Third Reich’s efforts in its development were certainly authentic, thus combining both schools of thought in the historiographical debate.”

That such honest scholarship is being published is encouraging and gives one hope that as the Second World War recedes in the rearview mirror, and the baseless allied propaganda used to denigrate National Socialism no longer rings in the ears of the general public, the truth will once again find a home in the hearts of our people. It is worth noting that, like the previous 1951 survey referenced above, another West German survey, decades later in 1985, found that 56% of respondents affirmed they had believed in National Socialism and still regarded it in a positive light.

At its core, National Socialism is constructive and positive, not destructive. Feel good about what you believe in. When you are hammered day-after-day by endless news cycles of violence and fear, remember you are working toward something better.

See, I told you this would be a positive article. I wish you all a Merry Christmas.

Amerika Erwache!

Housekeeping note: so we can celebrate Christmas with our families, there will not be a new post next week, however I do hope to get one more in under the wire before the end of the year.

SUBSCRIBE TO THIS BLOG

(It’s free, and mostly painless)

Leave a Reply