[Editor’s note: It’s that time again- I’m working on the next issue of The White Worker. This article will appear in the forthcoming issue.]

First Black female Supreme Court Justice,

Let’s not do that again.

With the recent slap down of DEI hire Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson by Justice Coney Barrett over the birthright citizenship issue, the overall role of the Supreme Court was in the news again, being another example of how the communist-left wannabes try to twist what should be a simple proposition into something it was never intended to be. In short, Barrett needed to remind mental-midget Jackson that the role of the Supreme Court is to rule on the constitutionality of actions and legislation. Period. Not to try and shape the laws of the land to fit the personal agendas of an individual justice and her minority homeboys.

Unfortunately, this is not a new debate. I was reminded of one of my favorite books: Race and Reason- A Yankee View by Carleton Putnam, and now seems as good a time as any- in light of the Supreme Court shenanigans and our current summer of “mostly peaceful” gatherings- to share it.

Mr. Putnam was an American lawyer, businessman, and writer. He graduated from Princeton University, received a Bachelor of Laws degree from Columbia Law School, and among his other accomplishments, served as the CEO of Delta Airlines and remained on that airline’s board of directors until his passing in 1998. His best know work, Race and Reason was written in 1961, just as the so-called “Civil Rights” movement was getting underway, and it does an extraordinary job of examining the race issue in the United States, explaining how the road our nation was heading down at that time was a mistake in the extreme by examining both historical and biological reasons why a mixed-race society would never work and, in fact, be a detriment to all concerned. Highly recommended.

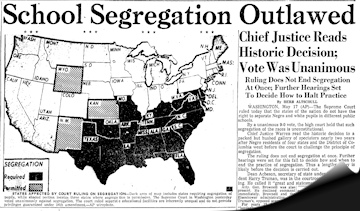

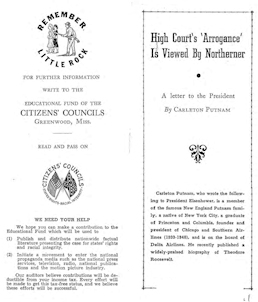

For our purposes, a look at one of the first issues addressed by Mr. Putnam, which he uses to set the stage, was his reaction to the 1954 desegregation decision (an egregious example of what we now call ‘social engineering’) and the subsequent 1958 Little Rock case of Cooper v. Aaron, wherein the Supreme Court overruled the Little Rock school board’s attempt to delay desegregation in the schools, the will of the people be damned.

What follows is a selection of the opening chapter, including an abridged version of an extraordinary letter Mr. Putnam wrote to President Eisenhower on the matter. I include the opening for narrative context, and the abridgment to facilitate our conversation, but naturally, the reader is encourage to view the work in its entirety. I located the book on the internet archive and was so impressed I printed and bound the work myself, only to discover later that, amazingly, it can still be found in print.

Without further ado, a selection from Chapter One and the Letter to the President, by Carleton Putnam, from Race and Reason: A Yankee View:

“…to the American West I owed a large part of my life’s motivation. From pack-trips across the Painted Desert in my college days, to camps in the Bad Lands of North Dakota where I began research on my biography of Roosevelt, I had known and loved the stage on which the pioneer played out the drama of the American Dream. It was not just a question of the sun setting beyond the Pass, nor the sound at night of wind rising in the forests of the Big Horn Mountains. These were important as symbols to the senses, but there were other scenes in the montage of memory— episodes involving people, from old prospectors and cowpunchers to women who had come to Arizona in covered wagons over the Santa Fe Trail —these were symbols of a different sort, figures of pride and self-reliance, and primordially American.

In a spiritual sense, of course, the Santa Fe Trail and the Oregon Trail had begun at Jamestown and Plymouth Rock, and had left me what I regarded as a personal heritage. My first American ancestors, on both my father’s and my mother’s side, had arrived in Massachusetts from England in the fourth decade of the seventeenth century. From Salem, to northern Vermont, to Saratoga and the Mohawk Valley, my father’s people migrated to the West of their day and bequeathed me a proprietary interest in a sunset and a frame of mind. Call it individualism, say it was rugged, nonetheless it was American in its time. There were certain traditions that were taken for granted, yet which passed by osmosis from father to son. A man expected the community to do for him only what there was no way of his doing for himself. When he asked the community to do what he ought to have done for himself, this was begging; it was begging because it meant another’s effort was making up his lack —and beggars were not popular on the frontier.

Nor was there a notion of equality in any sense except the equal chance. The frontier had its aristocracy of character to which one earned the right to belong. And the man with the bad reputation was not easily or quickly forgiven. I realize that today the frontier is history and that social conditions have changed. I do not see that the principles have changed… I would now only re-emphasize, in an age obsessed with novelty and change, the importance of our Anglo-American heritage, particularly in the field of moral values and basic principle. There are very few social experiments that have not been tried before, and there are absolutely no principles that have not been thoroughly tested. “Winds of change” do not alter these.

If I were asked to be specific, I would say that as time has gone on, I have been impressed with two fallacies that have crept into the thinking of Americans: the fallacy that men by weight of numbers can defy the moral law and lean increasingly upon other men under the guise of the State, and the fallacy that this dependence is justified by the supposed right of all men to share equally in everything.

It may seem strange, in the light of such views, that in June of 1954, when the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision burst upon the country, I did not react at once. Surely, here was a sharp departure from the past—a confusion of equality of opportunity and equality before the law, with social and cultural equality—as well as a clear challenge to other American principles.”

[Carleton here goes on to note that he, like many Northerners who were not directly impacted by the Supreme Court’s decision, was distracted with other matters and gave it little thought. But that changed four years later with the events in Little Rock, Arkansas. Having written a letter to an editor friend for publication expressing his displeasure with the Cooper v Aaron case, and it being well received, he decided to write on open letter to President Eisenhower. Imagine writing this letter for public consumption today, never mind sending it the President. It takes a paragraph or two before he really starts swinging, but thereafter the blows land hard and fast! -ed.]

“There was one man who could do more to correct the situation than any other, if he would, and that man was the President of the United States. Perhaps, in the maelstrom of other problems and activities, he had overlooked the real significance of the desegregation cases. Perhaps, if others as well as I wrote him, he might be led to see the reasonableness behind the Southern position. Then from the pulpit of the Presidency he might enlighten the nation. I began to wonder whether the best contribution I could make might not be to try to reach him with a new letter…and I set to work, helped by an opinion of Justice Frankfurter* in a case growing out of the Little Rock episode. Frankfurter’s views, printed in the Washington Post, had spoiled my breakfast a morning or two before, but now they gave me a starting point. On October 13, 1958 — I remember the occasion well because it was the climax of weeks of deliberation—I wrote as follows to President Eisenhower:

Washington, D. C.

Oct. 13, 1958

The Hon. Dwight D. Eisenhower

President of the United States

The White House

Washington 25, D. C.

My dear Mr. President:

A few days ago I was reading over Justice Frankfurter’s opinion in the recent Little Rock case. Three sentences in it tempt me to write you this letter. I am a Northerner, but I have spent a large part of my life as a business executive in the South. I have a law degree, but I am now engaged in historical writing. From this observation post I risk the presumption of a comment.

The sentences I wish to examine are these: “Local customs, however hardened by time, are not decreed in heaven. Habits and feelings they engender may be counteracted and moderated. Experience attests that such local habits and feelings will yield, gradually though this be, to law and education.”

It is my personal conviction that the local customs in this case were “hardened by time” for a very good reason, and that while they may not, as Frankfurter says, have been decreed in heaven, they come closer to it than the current view of the Supreme Court. I was particularly puzzled by Frankfurter’s remark that “the Constitution is not the formulation of the merely personal views of the members of this court.” Five minutes before the court’s desegregation decision, the Constitution meant one thing; five minutes later, it meant something else. Only one thing intervened, namely, an expression of the personal views of the members of the court.

It is not my purpose to dispute the point with which the greater part of Frankfurter’s opinion is concerned. The law must be obeyed. But I think the original desegregation decision was wrong, that it ought to be reversed, and that meanwhile every legal means should be found, not to disobey it, but to avoid it. Failing this, the situation should be corrected by constitutional amendment.

… In the matter of schools, rights to equal education are inseparably bound up with rights to freedom of association and, in the South at least, may require that both be considered simultaneously. (In using the word “association” here, I mean the right to associate with whom you please, and the right not to associate with whom you please.) Moreover, am I not correct in my recollection that it was the social stigma of segregation and its effect upon the Negro’s “mind and heart” to which the court objected as much as to any other, and thus that the court, in forcing the black man’s right to equal education was actually determined to violate the white man’s right to freedom of association?

In any case the crux of this issue would seem obvious: social status has to be earned. Or, to put it another way, equality of association has to be mutually agreed to and mutually desired. It cannot be achieved by legal fiat. Personally, I feel only affection for the Negro. But there are facts that have to be faced. Any man with two eyes in his head can observe a Negro settlement in the Congo, can study the pure-blooded African in his native habitat as he exists when left on his own resources, can compare this settlement with London or Paris, and can draw his own conclusions regarding relative levels of character and intelligence — or that combination of character and intelligence which is civilization.

Finally, he can inquire as to the number of pure-blooded blacks who have made contributions to great literature or engineering or medicine or philosophy or abstract science. (I do not include singing or athletics as these are not primarily matters of character and intelligence.) Nor is there any validity to the argument that the Negro “hasn’t been given a chance.” We were all in caves or trees originally. The progress which the pure-blooded black has made when left to himself, with a minimum of white help or hindrance, genetically or otherwise, can be measured today in the Congo.

…Throughout this controversy there has been frequent mention of the equality of man as a broad social objective. No proposition in recent years has been clouded by more loose thinking. Not many of us would care to enter a poetry contest with Keats, nor play chess with the national champion, nor set our character beside Albert Schweitzer’s. When we see the doctrine of equality contradicted everywhere around us in fact, it remains a mystery why so many of us continue to give it lip service in theory, and why we tolerate the vicious notion that status in any field need not be earned.

Pin down the man who uses the word “equality,” and at once the evasions and qualifications begin. As I recall, you, yourself, in a recent statement used some phrase to the effect that men were “equal in the sight of God.” I would be interested to know where in the Bible you get your authority for this conception. There is doubtless authority in Scripture for the concept of potential equality in the sight of God —after earning that status, and with various further qualifications —but where is the authority for the sort of ipso facto equality suggested by your context? The whole idea contradicts the basic tenet of the Christian and Jewish religions that status is earned through righteousness and is not an automatic matter. What is true of religion and righteousness is just as true of achievement in other fields. And what is true among individuals is just as true of averages among races.

Frankfurter closes his opinion with a quotation from Abraham Lincoln, to whom the Negro owes more than to any other man. I, too, would like to quote from Lincoln. At Charleston, Illinois, in September 1858 in a debate with Douglas, Lincoln said:

“I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races; I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor qualifying them to hold office … I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And in as much as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

… it seems clear that for 94 years — from the horrors of Reconstruction through the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision—the North has been trying to force the black man down the white Southerner’s throat, and it is a miracle that relations between the races in the South have progressed as well as they have…Indeed, there now seems little doubt that the court’s recent decision has set back the cause of the Negro in the South by a generation. He may force his way into white schools, but he will not force his way into white hearts nor earn the respect he seeks. What evolution was slowly and wisely achieving, revolution has now arrested, and the trail of bitterness will lead far.”

Felix Frankfurter

*Footnote: Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962. Born in Vienna to an Ashkenazi Jewish family, Frankfurter immigrated with his family to New York City at age 12. He graduated from Harvard Law School. His activities led the public to view him as a radical lawyer and supporter of radical principles. Encouraged by Jewish Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis to become more involved in Zionism, he lobbied President Wilson to support the Balfour Declaration, a British government statement supporting the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1918, he participated in the founding conference of the American Jewish Congress in Philadelphia and in 1919, served as a Zionist delegate to the Paris Peace Conference. In November 1919, he chaired a meeting in support of American recognition of the newly created Soviet Union. In 1920, Frankfurter helped to found the American Civil Liberties Union. At one point, J. Edgar Hoover began following Frankfurter as “the most dangerous man in the United States”, a “disseminator of Bolshevik propaganda”. He served as an advisor to Franklin D. Roosevelt upon the latter’s election starting in 1933, and was nominated to the Supreme Court in 1938 by Roosevelt. This gives the reader some idea of the type of person and their core beliefs that advocated for desegregation in the 1950s and 1960s. Even more, I’m still trying to get my mind around the fact that someone with these “credentials” could actually get on the Supreme Court: his being elevated to the highest court in the land instead of imprisoned or deported is emblematic of everything wrong in this so-called democracy.

Leave a Reply