We spend a lot of time looking at the symptoms of the decline of Western Civilization. Time to explore one of the causes.

First, I would like to thank you for taking the time to read this blog. You have my gratitude and appreciation. As you will see, you are becoming a breed apart. A rarity in the 21st century. For those that prefer to listen to the articles on the podcast, this applies to you as well: Listening to words is not far removed from reading them, as the same language processing part of the brain is actively engaged.

This is going to be a long post, so snuggle in, grab a cuppa, and take your time. Frankly, this is important to me, so I’m just going to run with it. Please forgive the indulgence. We’ll return to shorter, more “news” related fare soon enough. However, in a way, this lays the groundwork for a great many things covered by this blog. We spend a lot of time chasing our tails looking at symptoms. This speaks to causes. To some extent, it also serves as a “Part II” or follow-up to the article I wrote on April 1st of this year titled “This is How a Culture Dies”, and to a lesser extent the article published on August 13th , “Conscientiousness and National Socialism.”

At times it feels like I’m putting together the pieces of a very large puzzle, and this is a big piece.

What follows borrows heavily from a wonderful article by James Marriott, author of the Cultural Capital substack and writer for the Times, titled “The Dawn of the Post-literate Society and the End of Civilisation.“

In the past I’ve quoted articles in full, but Mr. Marriott’s is a long article and I wish to interject my insights and opinions as well, so consider this an abridged or hybrid version.

Ostensibly, his article, and this post, concerns itself with the decline in reading and literacy in the general population. But wait! It’s not as boring as it sounds. In reality, this has more to do with nothing less than the incipient demise of Western Civilization.

The decline in literacy plays into nearly every problem facing our society today: the growing inequality in wealth distribution; our streets being overrun by rainbow-haired automatons; racial tensions resulting from forcing disparate breeds of humans to live in close proximity; and colleges becoming nothing more than indoctrination centers for absurdly myopic social agendas, because all of these ills flourish in ignorance. More to the point, it speaks to the question of “how did we get here?”, a conundrum which has been one of the driving forces behind this blog since its inception.

Mr. Marriott sets the stage with a quote from the Jewish academic Neil Postman that, frankly, cuts to the heart of the matter:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book because there would be no one who wanted to read one.

— Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death

Just because Mr. Postman was Jewish doesn’t mean he was wrong. Published in 1985, Amusing Ourselves to Death argued that by expressing ideas through visual imagery, thereby short-circuiting the brain’s need to create that imagery itself, thus creating passive recipients out of formerly active participants , television reduces politics, news, history and other serious topics to entertainment. He worried that culture would decline if the people became an audience and their public business a “vaudeville act”. Given that the President of the United States was a former “reality” TV star speaks volumes. He also argued that television is destroying the “serious and rational public conversation” that was sustained for centuries by the printing press. Rather than the restricted information in George Orwell’s 1984, he claimed the flow of distraction we experience is akin to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. Walk that forward to the era of the cell phone and one could argue that he was not only right, but seriously underestimated the danger.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The age of print

It was one of the most important revolutions in modern history — and yet no blood was spilled, no bombs were thrown and no monarch was beheaded. Perhaps no great social transformation has ever been carried out so quietly. This one took place in armchairs, in libraries, in coffee houses and in clubs.

What happened was this: in the middle of the eighteenth century huge numbers of ordinary people began to read.

For the first couple of centuries after the invention of the printing press (c. 1440), reading remained largely an elite pursuit. But by the beginning of the 1700s, the expansion of education and an explosion of cheap books began to diffuse reading rapidly down through the middle classes and even into the lower ranks of society. People alive at the time understood that something momentous was going on. Suddenly it seemed that everyone was reading everywhere: men, women, children, the rich, the poor. Reading began to be described as a “fever”, an “epidemic”, a “craze”, a “madness”. As the historian Tim Blanning writes, “conservatives were appalled and progressives were delighted, that it was a habit that knew no social boundaries.”

This transformation is sometimes known as the “reading revolution”. It was an unprecedented democratization of information; the greatest transfer of knowledge into the hands of ordinary men and women in history.

In Britain only 6,000 books were published in the first decade of the eighteenth century; in the last decade of the same century the number of new titles was in excess of 56,000. More than half a million new publications appeared in German over the course of the 1700s. The historian Simon Schama has gone so far as to write that “literacy rates in eighteenth century France were much higher than in the late twentieth century United States”. Think about that for a moment.

Where readers had once read “intensively”, spending their lives reading and re-reading two or three books, the reading revolution popularised a new kind of “extensive” reading. People read everything they could get their hands on: newspapers, journals, history, philosophy, science, theology and literature. Books, pamphlets and periodicals poured off the presses. Think “Common Sense” by Thomas Paine, written to influence colonial Americans’ opinions in favor of liberty, or pamphleteers Camille Desmoulins and Jean-Paul Marat writing to mobilize and incite the French public against the monarchy, to say nothing of the importance of 20th century pamphlets by Gottfried Feder in helping to set the stage for National Socialist Germany, and you have some idea of the reach and influence reading had on the masses.

Print changed how people thought.

The world of print is orderly, logical and rational. In books, knowledge is classified, comprehended, connected and put in its place. Books make arguments, propose theses, develop ideas. “To engage with the written word”, the media theorist Neil Postman wrote, “means to follow a line of thought, which requires considerable powers of classifying, inference-making and reasoning.”

As Postman pointed out, it is no accident, that the growth of print culture in the eighteenth century was associated with the growing prestige of reason, hostility to superstition, the birth of capitalism, and the rapid development of science. Other historians have linked the eighteenth century explosion of literacy to the Enlightenment, the birth of human rights, the arrival of democracy and even the beginnings of the industrial revolution.

The world as we know it was forged in the reading revolution.

The counter revolution

Now, we are living through the counter-revolution.

More than three hundred years after the reading revolution ushered in a new era of human knowledge, books are dying.

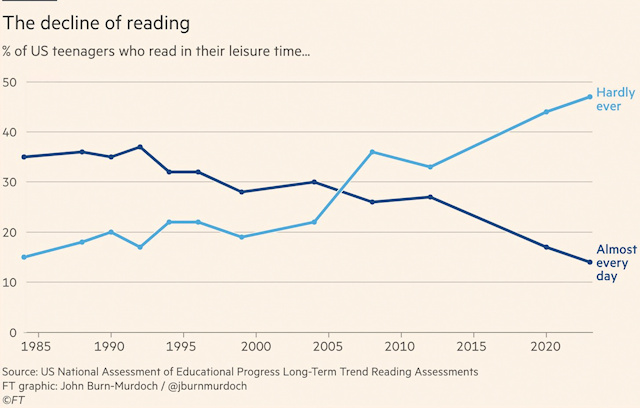

Numerous studies show that reading is in free-fall. Even the most pessimistic twentieth-century critics of the screen-age would have struggled to predict the scale of the present crisis.

In America, reading for pleasure has fallen by forty per cent in the last twenty years. In the UK, more than a third of adults say they have given up reading. The National Literacy Trust reports a “shocking and dispiriting” decline in children’s reading, which is now at its lowest level on record. The publishing industry is in crisis: as the author Alexander Larman writes, “books that once would have sold in the tens, even hundreds, of thousands are now lucky to sell in the mid-four figures.”

This is particularly worrisome for straight White male writers such as myself, who have been deliberately and increasingly censored over the last decade and a half. Out of sheer obstinacy I will continue to write what I think is important to share with the world and the future, knowing that it is becoming statistically unlikely anyone will every read it. Increasingly, it feels a bit like throwing a bottled message into the ocean of time. So be it.

In late 2024 the OECD (Organization for Economic-Cooperation and Development) published a report which found that literacy levels were “declining or stagnating” in most developed countries. Once upon a time a social scientist confronted with statistics like these might have guessed the cause was a societal crisis like a war or the collapse of the education system.

What happened was the smartphone, which was widely adopted in developed countries in the mid-2010s. Those years will be remembered as a watershed in human history.

Never before has there been a technology like the smartphone. Where previous entertainment technologies like cinema or television were intended to capture their audience’s attention for a period, the smartphone demands your entire life. Phones are designed to be hyper-addictive, hooking users on a diet of pointless notifications, inane short-form videos and social media rage bait.

The average person now spends seven hours a day staring at a screen. For Gen Z the figure is nine hours. A recent article in

The Times found that on average modern students are destined to spend 25 years of their waking lives scrolling on screens.

If the reading revolution represented the greatest transfer of knowledge to ordinary men and women in history, the screen revolution represents the greatest theft of knowledge from ordinary people in history.

Our universities are at the front line of this crisis. They are now teaching their first truly “post-literate” cohorts of students, who have grown up almost entirely in the world of short-form video, computer games, addictive algorithms (and, increasingly, AI).

Because a ubiquitous mobile internet has destroyed these students’ attention spans and restricted the growth of their vocabularies, the rich and detailed knowledge stored in books is becoming inaccessible to many of them. A study of English literature students at American universities found that they were unable to understand the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’s novel Bleak House — a book that was once regularly read by children. Contrast this with George Orwell reporting on a newly-published study of children’s reading habits in 1940, in which he found that children were “voluntarily” reading works by Charles Dickens, Daniel Defoe, Robert Louis Stevenson, GK Chesterton and Shakespeare. These children, he noted, were “aged between 12-15 and belonged to the poorest class in the community”.

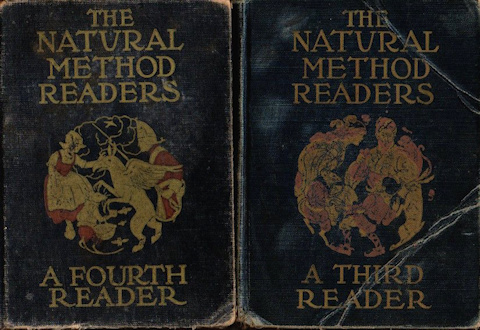

Somewhat more recently, when I was a child, my father gave me two books to read that his parents had given him when he was young: the “Natural Method Readers”, numbers Three and Four, published in 1916 and 1917 respectively. Their purpose was to teach children how to read beyond phonics and word memorization and were intended for children in the 6 to 8 age range. A cursory glance at the table of contents is telling:

The Third Reader featured works by Wordsworth, Longfellow, Robert L. Stevenson, Norse myths, the Grimm Brothers, and the Bible among others. The Fourth Reader added to the above works with Hawthorne, Hans Christian Andersen, Tennyson, Lewis Carrol, and even “Under the Greenwood Tree” a song from William Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, specifically Act 2, Scene 5, presented as a poem.

Again, these were for children to read. And we did.

Now, evidently, the school bus has been driven off the cliff. One professor at Columbia University laments that 20 years ago, he could engaging in sophisticated discussions of Pride and Prejudice one week and Crime and Punishment the next. Now his students tell him up front that the reading load feels impossible. It’s not just the frenetic pace; they struggle to attend to small details while keeping track of the overall plot. Said another source: “Most of our students are functionally illiterate”.

This reminds me of an episode I experienced in college. Like many of my generation, I took the “long route” getting my degree. Life happens. I started in the late 1980’s after I got out of the Army, but didn’t finish until nearly the end of the 90’s after my first marriage. I do not recall there being any significant disconnect between the students’ abilities and the professors’ expectations when I began. However, ten years later, as I neared graduation and found myself in a 300 or 400 level history course (roughly Junior or Senior level), I was amazed when the professor, in frustration, handed back a round of papers, wiped the board clean and said, “We are going to stop here. For the next week we are going to study basic composition. How many of you know what a paragraph is?”

And this was an upper division college course. For the record, I knew. Granted, this was before the smart phone, but the technological distractions of the era (cell phones, home computers, cable television, etc) and the consequence of catering to the lowest common denominator among students were already prevalent.

With the roiling campuses and the “cause of the day” riots so popular on American streets today, one fears this dumbing down may be by design. It certainly is not without consequence. As stated in a recent American Thinker article:

American Leftism is a unique amalgamation of Marxism, Darwinism, and oligarchism that requires an army of brain-dead acolytes who dwell in a state of permanent adolescence. The vast majority of these foot soldiers do not understand that the leadership of their movement consists of avowed Marxists determined to establish a one-party socialist oligarchy in which they will be viewed no differently than the rest of the unwashed masses. “

In short, the transmission of knowledge — the most ancient function of the university — is breaking down in front of our eyes and we are seeing the results in our streets. Writers like Shakespeare, Milton and Jane Austen whose works have been handed on for centuries can no longer reach the next generation of readers because they are losing the ability to understand them.

The tradition of learning is like a precious golden thread of knowledge running through human history linking reader to reader through time. It is a shared experience, a conversation that spans generations- often referred to as “The Great Conversation”, and a cultural foundation. It last snapped during the collapse of the Western Roman Empire as the barbarian tides beat against the frontier, cities shrank and libraries burned or decayed. As the world of Rome’s educated elite fell apart, many writers and works of literature passed out of human memory — either to be lost forever or to be rediscovered hundreds of years later in the Renaissance.

That golden thread is breaking for the second time.

An intellectual tragedy

It is not just knowledge that is being lost, but the ability to think as well.

The collapse of reading is driving declines in various measures of cognitive ability. Reading is associated with a number of cognitive benefits including improved memory and attention span, better analytical thinking, improved verbal fluency, and lower rates of cognitive decline in later life.

After the introduction of smartphones in the mid-2010s, global PISA scores — the most famous international measure of student ability, rather like an international SAT for 15-year-olds — began to decline. The United States currently ranks 21st world-wide, behind nearly all of Europe and Asia.

As John Burn Murdoch writes in the Financial Times, students increasingly tell surveys that they struggle to think, learn and concentrate. You will notice the tell-tale mid-2010s inflection point:

“The Monitoring the Future study has been asking 18-year-olds whether they have difficulty thinking, concentrating or learning new things. The share of final year high school students who report difficulties was stable throughout the 1990s and 2000s, but began a rapid upward climb in the mid-2010s. “

Adults tested also showed a nearly identical decline over the same time-frame. Most intriguing — and alarming — is the case of IQ, which rose consistently throughout the twentieth century (the so-called “Flynn effect”) but which now seems to have begun to fall.

The Damage Done – A World Without Mind

The result of declining literacy and IQ is not only the loss of information and intelligence, but a tragic impoverishing of the human experience. For centuries, almost all educated and intelligent people have believed that literature and learning are among the highest purposes and deepest consolations of human existence.

The classics have been preserved over the centuries because they contain, in Matthew Arnold’s famous phrase, “the best that has been thought and said”.

The greatest novels and poems enrich our sense of the human experience by imaginatively putting us inside other minds and taking us to other times and other places. By reading non-fiction — science, history, philosophy, travel writing — we become deeply acquainted with our place in the extraordinary and complicated world we are privileged to inhabit. In other words, it gives our life greater context.

Smartphones are robbing of us of these consolations.

The epidemic of anxiety, depression and purposelessness afflicting young people in the twenty-first century is often linked to the isolation and negative social comparison fostered by smartphones.

It is also a direct product of the pointlessness, fragmentation and triviality of the culture of the screen which is wholly unequipped to speak to the deep human needs for curiosity, narrative, deep attention and artistic fulfillment.

This draining away of culture, critical thinking and intelligence represents a tragic loss of human potential and human flourishing. It is also one of the major challenges facing modern societies. Our vast, interconnected, tolerant and technologically advanced civilization is founded on the complex, rational kinds of thinking fostered by literacy.

As Walter Ong writes in his book Orality and Literacy, certain kinds of complex and logical thinking simply cannot be achieved without reading and writing. It is virtually impossible to develop a detailed and logical argument in spontaneous speech — you would get lost, lose your thread, contradict yourself, and confuse your audience trying to re-phrase ineptly expressed points.

As an extreme example, think of somebody trying to simply speak a famous work of philosophy. Say, Kant’s 900-page The Critique of Pure Reason or Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus or Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. It would be impossible to do. And also impossible to listen to.

To produce his great work Kant had to write down his ideas, scratch them out, think about them, refine them and then rework them over many years so they added up into a persuasive and logical whole. To properly understand the book you have to be able to have it in front of you so you can re-read bits you don’t understand, check logical connections and meditate on important passages until you really take them in. This kind of advanced thinking is inseparable from reading and writing.

Perceptive listeners of my podcast might note that it sounds like I am reading the content. That is because I am, reading what I have written for this blog. I have found trying to do it “off the top of my head” to be nothing but a mumbling, bumbling, frustrating experience. The blog, in turn, goes through a convoluted process similar to that noted above for Kant where by I have two documents open at the same time, one for notes the other for content, and I bounce back and forth between the two until I have a rough draft. In a way, every article is the same: It starts with an agenda or premise based on preliminary information requiring further research, elaborates on that premise and supports it with facts, then draws a conclusion based on the information used to substantiate or support the premise. Essentially, it’s composition 101. What is interesting to me is that when I try to verbalize the same argument or conclusion sitting around the coffee table, it never, ever, comes out as coherent, persuasive, or convincing, even after I’ve written the post. This is because it lacks the narrative flow and logical organization found in the written version, every time.

Deep Thoughts

The classicist Eric Havelock argued that the arrival of literacy in ancient Greece was the catalyst for the birth of philosophy. It also allowed for reflection and criticism. As Neil Postman puts it in Amusing Ourselves to Death:

Philosophy cannot exist without criticism . . . writing makes it possible and convenient to subject thought to a continuous and concentrated scrutiny. Writing freezes speech and in so doing gives birth to the grammarian, the logician, the rhetorician, the historian, the scientist-all those who must hold language before them so that they can see what it means, where it errs, and where it is leading.

Adolf Hitler, of course, had little use for cloistered philosophy and endless book-learning. He much preferred the “boots on the ground”, lived experience of National Socialism. But it should also be remembered that he was a voracious reader who did not invent National Socialism out of whole cloth. He drew from, and understood the importance of, those philosophers and scientists that came before him, to say nothing of his remarkable grasp of history and technology. As he explains in Volume 1, Chapter 2 of Mein Kampf, (and as found in last month’s The White Worker), reading widely and critically was essential to the formation of his Worldview. He cited Greek philosopher Heraclitus as the foundation of his doctrine of perpetual struggle, a theme which wasexpanded upon by Nietzsche, who in turn, was another philosopher Hitler read widely during his Vienna years.

Not only philosophy but the entire intellectual infrastructure of modern civilization depends on the kinds of complex thinking inseparable from reading and writing, for example: serious historical writing, scientific theorems, detailed policy proposals and the kinds of rigorous and dispassionate political debate conducted in books and magazines.

These forms of advanced thought provide the intellectual underpinnings of modernity. If our world feels unstable at the moment — like the ground is shifting beneath us — it is because those underpinnings are falling to pieces underneath our feet.

As you have probably noticed, the world of the screen is going to be much a choppier place than the world of print: more emotional, more angry, more chaotic.

Walter Ong emphasized that writing cools and rationalizes thought. If you want to make your case in person or in a TikTok video you have innumerable means for bypassing logical argument. You can shout and weep and charm your audience into submission. You can play emotive music or show harrowing images. Such appeals to sentiment are not rational, but human beings are not perfectly rational animals and are inclined to be persuaded by them.

Without the emotive array of logic-defeating appeals available to podcasters and YouTubers, authors are much more reliant on reason alone, condemned to painfully piece their arguments together sentence by sentence. A pain I experience every week.

This is why, as Ong observed, that pre-literate “oral” societies often strike visitors from literate countries as remarkably mystical, emotional, and antagonistic in their discourse and thinking. As books die, we seem to be returning to these “oral” habits of thought. Our discourse is collapsing into panic, hatred and tribal warfare. Anti-scientific thought thrives at the highest level of the American government. Promoters of irrationality and conspiracy theories find vast and credulous audiences online.

Laid out on the page their arguments would seem absurd. On the screen, they are persuasive to many people. We may be about to find out that it is not possible to run the most advanced civilization in the history of the planet with the intellectual apparatus of a pre-literate society.

The End of Creativity

The age of print was characterized by unprecedented progress, change, and cultural richness. Reading is a foundation stone of the creativity and innovation that is fundamental to modernity.

People of influence read. For example: Teddy Roosevelt claimed to read a book a day, Winston Churchill set himself an ambitious program of reading in philosophy, economics and history as a young man and continued to read voraciously throughout his life. Clement Attlee recalled that he read four books a week as a schoolboy. Thomas Edison read deeply throughout his life. So did Charles Darwin. So did Albert Einstein. Ironically, even Elon Musk claims that he was “raised by books” (although, that may not be the endorsement we are looking for).

The Great Conversation is the ongoing process of writers and thinkers referencing, building on, and refining the work of their predecessors. This process is characterized by writers in the Western canon making comparisons and allusions to the works of earlier writers and thinkers.

Reading enriches creative work by giving men and women of genius access to the vast and priceless trove of knowledge preserved in books — “the best that has been thought and said”. The discipline of reading equips them with the analytical tools to interrogate, refine and revolutionize that tradition.

As Newton said in his letter to Robert Hooke, “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

Looking Backward (with apologies to Edward Bellamy)

The invention of the printing press helped to catalyze a series of cultural revolutions which forged the modern world: the Renaissance, the Reformation and the scientific revolution. Other historians would add the Enlightenment, the birth of human rights and the industrial revolution. With the invention of printing, students had increased access to books allowing “bright undergraduates to reach beyond their teachers’ grasp. Gifted students no longer needed to sit at the feet of a given master in order to learn a language or academic skill.” And so, students who took advantage of technical texts which served as silent instructors were less likely to defer to traditional authority and more receptive to innovating trends. Young minds provided with updated editions, especially of mathematical texts, began to surpass not only their own elders but the wisdom of ancients as well.

Modern students who are unable to read are once more reliant on the authority of their teachers and are less capable of racing ahead, innovating and questioning orthodoxies. Indeed, the are increasingly becoming moronic automatons mindlessly regurgitating the thin intellectual gruel they have been fed, often Marxist in flavor.

These students are just one symptom of the stagnant culture of the screen age which is characterized by simplicity, repetitiveness and shallowness. Its symptoms are observable all around us. Our culture is being transformed into a smartphone wasteland.

Cut off from the cultural riches of the past we are condemned to live in a narcissistic eternal present. Deprived of the critical tools to question and develop the insights of those who went before us, we are condemned to endlessly repeat and pastiche ourselves, superhero film by superhero film, repetitive pop song by repetitive pop song.

Into The Moronic Inferno

The big tech companies like to see themselves as invested in spreading knowledge and curiosity. In fact in order to survive they must promote stupidity. The tech oligarchs have just as much of a stake in the ignorance of the population as the most reactionary feudal autocrat. Dumb rage and partisan thinking keep us glued to our phones.

And where the old European monarchies had to (often ineptly) try to censor dangerously critical material, the big tech companies ensure our ignorance much more effectively by flooding our culture with rage, distraction and irrelevance.

These companies are actively working to destroy human enlightenment and usher in a new dark age.

The screen revolution will shape our politics as profoundly as the reading revolution of the eighteenth century.

Without the knowledge and without the critical thinking skills instilled by print, many of the citizens of modern democracies find themselves as helpless and as credulous as medieval peasants — moved by irrational appeals and prone to mob thinking. The world after print increasingly resembles the world before print.

As power, wealth and knowledge concentrate at the top of society, an angry, divided and uninformed public lacks a way to understand or analyze or criticize or change what is going on. Instead more and more people are impressed by the kinds of highly emotional charismatic and mystical appeals that were the foundation of power in the age before widespread literacy. Think “Make America Great Again.” It’s a wonderful slogan. Pithy. Easy to remember. But what does it actually mean? The short answer is: nothing. It’s a blank screen upon which people can project whatever they want to see. The longer answer can be found in Project 2025. But how many people wearing MAGA hats have actually read that?

Ultimately, this speaks directly to one of the fundamental missions of the American Nazi Party: education. As tech companies wipe out literacy and middle class jobs, we may find ourselves in a second feudal age. Only by keeping our brothers and sisters informed and educated can we hold back the tide of oligarchic enslavement.

What can you do? Read. Encourage those you meet to read: this blog, the ANP website, Mein Kampf, the books of George Lincoln Rockwell, the classics, anything which challenges the steady march to ignorance our society is on. Read The White Worker (the June-July issue included an anonymous online survey in the “From the Editor” section. Not one person responded. I can only surmise that 1) no one was willing to take the survey, or 2) no one read the section, which raises the question of how much of what we write for our cause actually gets read).

Turn off the phone, open a book. Go to the book store. Take your kids to a book store. Read before going to bed instead of surfing the phone. Over time, reading becomes a habit like anything else. For myself, I find I cannot sit for any length of time without something to read, nor “wind down” for the evening without spending an hour or more with a book. Not that I’m special- it’s just a habit my body and mind have come to expect. Make time to read. If need be, listen to an audio version of a classic work. Be part of the Great Conversation.

Reading also speaks, directly, to the preservation of our race. By catering to the lowest-common-denominator for decades, academia, big tech, and our government are slowly erasing our history and heritage by making White children (and increasingly, adults) unable to access their past. Without this context and the knowledge that reading can provide, to say nothing of the analytical skills it helps to hone, our people feel increasingly lost, isolated, and adrift. We must not let the globalists controlling the click-bait content on our phones to be the ones that fill the void.

Thank you for reading this blog.

Amerika Erwache!

SUBSCRIBE TO THIS BLOG

(It’s free, and mostly painless)

Leave a Reply