There was an important anniversary last week, but if your primary source of information is some form of the mainstream media you were probably not aware of it.

100 years ago this month, most sources say July 18th, Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf was published.

Given the events that followed its publication, one would think some mention of the anniversary was called for. And yet, as near as I can ascertain, not one major news outlet in the United States marked the event- with the exception of NPR. NPR’s story, a report on All Things Considered by a gay Jordanian Jew, was actually using the anniversary to promote a new “documentary” titled: “Hitler’s Mein Kampf: Prelude to the Holocaust.” Naturally. That’s what the worlds needs: another so-called “documentary” on the Holocaust® (registered trademark Shoah Scam, Inc., all-rights reserved). One has to wonder how much money Jews have made from the publication of Mein Kampf, from pseudo- documentaries, books, movies, and using it as the excuse to play the “victim” card to foster pecuniary gain. A number of other, smaller, non-print outlets and platforms marked the anniversary, but with predictable bias.

Overseas, it was slightly different: in the UK, no less a publication than The Times marked the event with an article on July 5 titled “Mein Kampf at 100 — why the most reviled book in history still haunts us”; written by a Jew, of course. And again using it to promote another documentary, by a Jew, on BBC 4. Don’t get me wrong: Jews are certainly entitled to their opinion and free to express it. But let’s be honest, if you are looking for an unbiased report on any aspect pertaining to Hitler or the Third Reich, asking a Jew to write it is, shall we say…problematic. And yet, that is who the few outlets that actually bothered to mark the event turned to. As far as the media is concerned, if you’re Jewish, you are automatically an authority on all things related to Hitler and the Third Reich.

So for fairness, it only seems appropriate that we who have a more personal interest in and heartfelt appreciation for Mein Kampf should mark the event as well. It is an extraordinary work for a variety of reasons: it is part autobiography and part political testament; part narrative, part manifesto or elaboration of his Worldview; and part history. What’s more, it is unassuming and honest, written as Hitler spoke, not a polished scholastic paper submitted for peer review- and all the more powerful for it. It has been suppressed, condemned, mischaracterized, disparaged, and poorly translated (until recently- we’ll come to that in a moment). And yet, it remains nothing short of required reading.

Of Sales and Readers

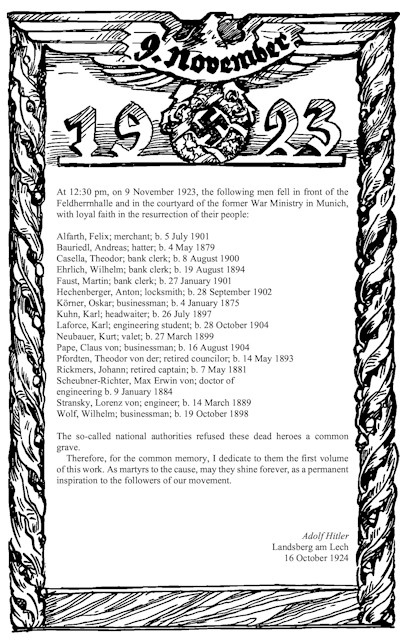

One of the more popular myths told about Mein Kampf is that it is one of the best sold books that no one ever read. This is a lie told by those who did not read it while still having the audacity to condemn it for what it says. The first volume was written while Hitler spent 264 days in Landsberg prison and was published in 1925, followed by a second volume written in and published in 1926. When the first volume was published it was comparatively expensive (12 Marks). But the 10,000 copies of the first edition sold within a few months.

Think about that for a moment: 10,000 copies of an expensive book, written by a someone in prison, banned from speaking, and the leader of an outlawed and fragmented political party. A second edition went into print in December 1925, and it too sold out. When the second volume was published on 10 December 1926, also with 10,000 copies for a start, it too sold out and quickly required additional editions. From May 7, 1930 onward, both volumes were combined into a so-called “people’s edition” for eight Reichsmarks in one volume. When we speak of Mein Kampf today, people usually think of this one-volume book.

(1939 Jubilee edition)

Before 1932, more than 200,000 copies of Mein Kampf were sold. This was a high level of distribution for a political book at the time, and runs contrary to the usual narrative that people were forced to buy the book. They weren’t. Hitler wasn’t even close to being in power when the book sold as well as it did. Still, sales increased significantly as the Weimar Regime collapsed and the masses wanted to know more about the Führer and his message: From the beginning of 1932 and in the period immediately after Hitler became chancellor in January 1933 around one million copies were sold and surviving records show that a significant number of copies were borrowed from public libraries, further indicating sincere interest. One estimate places the total number of German copies sold between 1925 and 1945 at 12,450,000.

Mein Kampf‘s early success alone, and the large number of later editions and copies distributed, show that the book was disseminated and its message understood at a far higher rate than we have been led to believe. The perpetuation of the “no one read it” myth is, to some extent, likely by design and the result of suppression: no new translations of Mein Kampf were allowed after the War until 2016. But it is also the result of what we would now call “sampling bias”: the American military administration conducted two representative surveys in their occupation zone in February 1946 and November 1947. In 1946, only seven percent of the interviewees claimed to have read the book in full and a further sixteen percent had read parts of it. In 1947, the figures went down to five percent for the entire text and fourteen percent for partial reading. Thus, the conclusion reached and promoted by the Allies in an attempt to denigrate Hitler’s memory was that no one actually read his book, Mein Kampf.

However, the obvious is now acknowledged: interviewing people to see if they had read Hitler’s book at a time when the Allies were still actively arresting former Party members, conducting the Nuremberg Show Trials, and trying to “denazify” the German people, was not going to promote honest, unbiased responses. Like anyone under similar circumstances, the Germans told the interviewers what they thought they wanted to hear to keep out of trouble.

Translations, Writing Style, and Readability

Another common observation is that Mein Kampf is hard to read. And to some extent, this is true. But there are a number of things that need to be taken into account before accepting this statement as valid. First, a couple of obvious points: as mentioned previously, it is not a novel. It is part autobiography, part history, and partly a political document. It’s not light reading. As you might expect when confronted with this sort of text, it requires focus.

Furthermore, the intended audience at the time is different from those reading the text today: Hitler’s Germans would have been able to read between the lines at subtleties all but the most informed historians would miss today, and they were grounded in common experiences and social struggles we can only begin to understand: The shells had stopped falling on the Western Front a mere six years before Mein Kampf was published, and every reader would have been aware of the Communist efforts to take over local governments and trade-unions.

In short, although in general terms what Hitler has to say in Mein Kampf is just as important today, to us, as it was to the Germans of his time, an understanding of the historical context and references goes a long way toward making Mein Kampf more enjoyable and engaging reading. In addition, it is important to remember that Hitler was not a writer, he was a speaker. He preferred action over endless hours on the typewriter. Had he not been arrested in November, 1923, and barred from speaking after he got out of Landsberg, it’s entirely possible Mein Kampf would never have been written. Frankly, he was too busy.

“the book sounds honest and brave. Only the style is sometimes loathsome. You have to be very broad-minded for it. He writes as he speaks. It sounds with immediate impact, but also often unsophisticated.” ~ from the diary of Joseph Goebbles

This quote leads us to the second point: the writing style. News flash: Mein Kampf was originally written in German. Unless you are reading the original text , you are reading someone else’s interpretation of it. This is where a good translator comes in. If English speakers have had trouble reading Mein Kampf, that is largely because the translations have been so poor. Translation is part art and part science. Language involves nuance and layered meaning. Words are not widgets easily swapped, and one word can mean many different things, often at the same time. Take for example the word “great”. You might ask a person how they like their new car, and he might reply, “It’s great!” and we English speakers all know what he means. However, translated, that response in a different language could be misconstrued to read “It’s large!”, or “It’s significant”, or even “It’s a lot.” In short, translation is not a case of “plug-n-play”. Meaning matters.

Mein Kampf was translated into at least eighteen foreign languages before 1945. The quality of these translations varied and was largely determined by whether the translator was sympathetic or opposed to Adolf Hitler. Interestingly, the earliest translations before 1945 were produced in the Soviet Union and the English language world. A Russian translated Mein Kampf in 1933 while in “internal exile”-likely code for Siberia- “as a sign of loyalty to the party leadership.”- doubtless he thought he was doing them a favor. But it was not published at the time, even though its text seems to have been shared among the highest Communist Party leaders. It took until 1992 before text was published in full, only to be banned again in 2002 shortly after Putin came to power. Hmm.

As for the English translations, frankly, it’s a topic almost too convoluted to get into in this brief space. There were many attempts, some worse than others, none very good, and all reflect the bias of their translators. The most commonly found today are the Murphy, Manheim, Stalag, and Ford editions. Only the Ford edition was published after the war. However, to the present day, the Manheim version functions as the ‘official’ translation of Mein Kampf: it is the one quoted by nearly all academics and journalists, even though (or perhaps because) it is highly biased. In addition, it is written in a rather archaic or old-fashioned British style, again serving to distance and confuse modern readers. It’s almost as though the publishing houses don’t want you to read Mein Kampf….

This is unfortunate, to say the least. It is almost as if the publishers intended, or at least preferred, that the translations be difficult to read. Certainly this limits the circulation of Hitler’s ideas, and makes it easier to dismiss them–a convenient situation, for the book’s many critics.” – Thomas Dalton

As readers of The White Worker know, we publish a “Monthly Mein Kampf ” column in each edition- typically a selection from that work with some bearing on the events of the day or of general relevance to the preservation of the White race. When HAKoehler asked me to take over the editorial duties for that publication, I asked him which version of Mein Kampf he preferred, as I liked the Dalton translation (more on that shortly). I think his response sums up the problems with the available translations nicely:

Yes, Dalton.

The British Murphy translation is incomplete, and was supervised by a Jewess editor. The Manheim translation is not bad for a Jew who hated the task, his first such commission as a translator for Houghton-Mifflin, but it has several intentional distortions here and there, for example: AH does not use the word “kike” anywhere. Nor the word “swastika”, it’s Hakenkreuz, hooks-cross. The Stalag edition is a good high school attempt by a German with some English instruction, but wooden. The Ford translation is a vanity production, just horrid. –hak (for HAKenkreuz!)”

Perhaps those in power preferred inadequate and poorly translated versions of Mein Kampf to dominate the market in an effort to suppress its readership. Upon Hitler’s death he was considered to be a citizen of Munich, where he had owned a flat and officially lived since the 1920s. As with the rest of Hitler’s property, US Occupation Authorities seized the rights of Mein Kampf from his publisher. In 1948, the rights were transferred to the Free State of Bavaria and in 1965 the Bavarian Ministry of Finance took over responsibility. The Ministry consistently refused to allow any re-publication of the text, though existing translations could be reprinted in new editions (except in Germany). The copyright, however, expired in 2016.

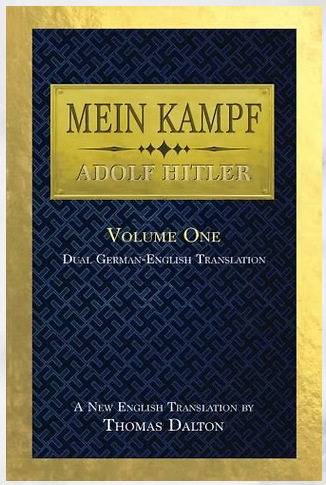

In 2018, author Thomas Dalton published a new translation of Mein Kampf. He chose as his source the original 1927 edition that, as noted above, combined Volumes I & II.

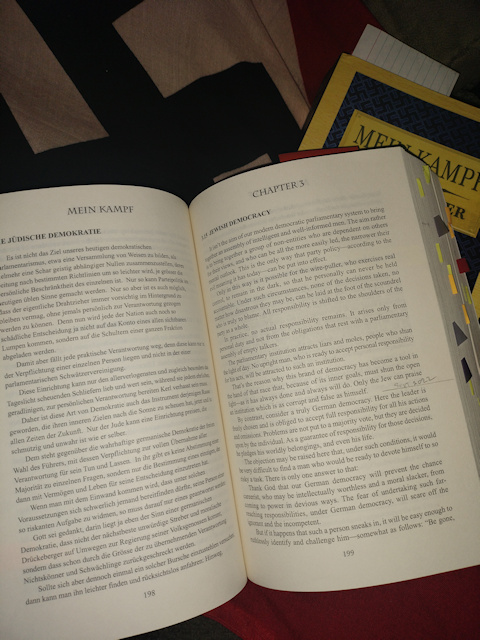

One notable “change” Mr. Dalton brought to the work was organization. Interestingly, it now reads much more like it was probably dictated and written: one section or topic at a time, perhaps one or two per day, with hard breaks between them. This alone makes it much easier to understand, as it instinctively reminds the reader that he or she is not reading a novel, but a thoughtful work examining in detail many subjects, not all of which are interrelated. However, Hitler did use Chapters breaks and section headings, which Dalton retains (as the other works do not). These headings have been translated and inserted at the appropriate points, directly in the text. This simple change greatly improves readability, by clearly organizing the narrative and breaking up long textual passages.

In addition, as Mr. Dalton explains, “Much emphasis has been placed here on readability, without sacrificing accuracy. The English text reads smoothly and naturally. Also, numerous contractions have been employed: it’s, I’m, isn’t, and so on. This again improves readability, and more closely matches the first-person ‘dictation’ style of the original.”

This is critical. Here are two examples. This is taken from Chapter 2, Section 18 “Politicization of the Trade Unions”- although you wouldn’t know that if you were reading the Manheim edition, as it lacks section headings:

Manheim Translation:

Proportionately as the political bourgeoisie did not understand, or rather did not want to understand, the importance of trade-union organization, and resisted it, the Social Democrats took possession of the contested movement. Thus, far-sightedly it created a firm foundation which on several critical occasions has stood up when all other supports failed. In this way the intrinsic purpose was gradually submerged, making place for new aims.

It never occurred to the Social Democrats to limit the movement they had thus captured to its original task.

Dalton Translation of the same section:

The political bourgeoisie failed to understand–or rather, did not wish to understand–the importance of the trade union movement. The Social Democrats thereby took advantage of this mistake and pulled the labor movement under their sole protection, without any protest. Thus they established for themselves a solid foundation of support. Correspondingly, the real purpose of the union movement gradually fell into oblivion, and was replaced by new objectives.

It never occurred to the Social Democrats that they should respect the original purpose of the union movement.

If you squint really hard, you can see that the Manheim translation says essentially the same thing as the Dalton translation. But which would your rather read? Me too. In fact, being the doubting Thomas (no pun intended) that I am, I ordered the Thomas Dalton Dual-Translation: It has the original German text on one page, and the translation on the facing page. After spending sometime going back and forth, I believe the Dalton translation to be artful, accurate, and highly readable. While still being faithful to the text, Mr. Dalton understands that translation is more than just words, it must convey the meaning as well.

As Mr. Dalton himself says:

The book has been functionally censored in the West for decades. And when academics or journalists are compelled to address it, it is always in slanderous and defamatory terms. This is the clearest demonstration that something important is happening in this text–something that most would rather leave unknown...Mein Kampf is one man’s assessment of history and vision for the future. It is blunt; it is harsh; it is unapologetic. It does not comply with contemporary standards of politeness, objectivity, and political correctness. It sounds offensive to sensitive modern ears. But the book is undeniably important. It is more consequential than perhaps any other political work in history. It deserves to be read, in a clear and unbiased translation. And each reader will then be free to determine its ultimate value and meaning for themselves.”

Happy Anniversary! Do yourself a favor, and read some Mein Kampf. If you only have access to an older translation, remember to look past the words to find the underlying meaning. If you want to try the Dalton translation- which is recommended- it can be found on the Internet Archive. However, I urge you to purchase the work as well to support the translator. Willing to drop the bias and provide an honest translation, we need more people like him putting pen to paper.

Amerika Erwache!

Leave a Reply