Born April 20, 1889, Today marks Adolf Hitler’s 135 birthday. Herzlichen Glückwunsch zum Geburtstag Mein Führer!

To recognize the occasion, we naturally want to take note his achievements and highlight aspects of his remarkable life. But let us shift the spotlight a little bit, and look at an area of his life often glossed-over or mentioned only in passing: his service in World War I.

When one talks of Adolf Hitler to the average person, the images that most often come to mind are of an older Hitler, surrounded by staff, giving orders and deciding the fate of Europe and the world.

If his involvement in World War I is raised at all, too often it is in the context of a footnote and dismissed with assumptions: he was a message carrier out of harms way, he was a coward, he was a draft dodger, etc.

None of these assumptions are true. In fact, quite the opposite.

When war was declared in 1914, Hitler was living in Munich. Although Austrian-German by birth, he had no desire to serve in the Austrian Army as he viewed Austria (rightly) as a racial amalgam, a polyglot State undeserving of his devotion. His heart lay with Germany and her Volk. On the very day that Germany declared war on France, Hitler appealed directly to Ludwig III of Bavaria requesting permission to enlist in his army (Bavaria, though part of the German Empire, retained independent sovereignty until 1918). He was accepted and eventually assigned to the 16th Bavarian Infantry Reserve Regiment.

After (rudimentary) training, the Regiment was sent to the front. Here Hitler endured the classic infantryman’s misery: long marches in awful weather, including an 11 hour march in continuous rain. Anyone who has served carrying a heavy rucksack and rifle while walking hour after hour in government issue boots knows how painful this can be.

Shortly thereafter, Hitler and his comrades were thrust into the First Battle of Ypres.

Having been issued old style leather caps instead of helmets, Hitler’s regiment was initially mistaken for British soldiers by Württemburg troops on their right and took withering friendly fire. There were many casualties, including the regimental commander.

Hitler and another soldier, Schmidt, tossing off their caps, sprinted back to headquarters to inform them of the confusion.

“After this incident the attack proper began, with the British dropping artillery shells into the assaulting columns. The men crawled into shallow dugouts and shell holes to escape the flying shrapnel, before racing to a small farmhouse in the middle of the field and crawling into a ditch. During this assault, Hitler’s platoon leader was killed, as were most of the noncommissioned officers. In all, it took five bloody assaults to take the edge of the forest. The final assault ended in hand-to-hand combat, and Hitler was surprised when he jumped into the British trench and made a soft landing—he had landed on a British corpse. “

(source: warfare history network)

For his bravery and conduct, Hitler was recommended for the post of regimental runner. Both he and Schmidt were recommended for the Iron Cross (though neither received it for this particular action).

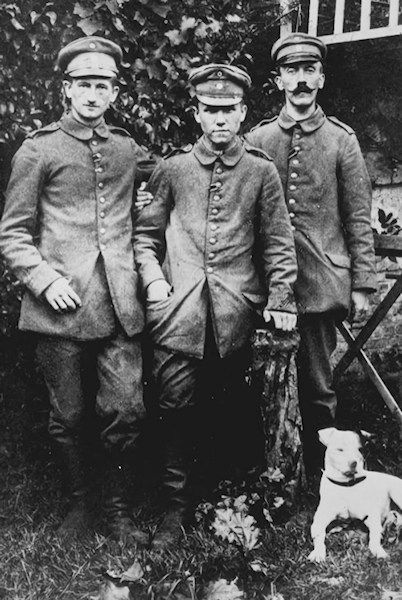

On November 3, Hitler and two other comrades, including Schmidt, were officially assigned as dispatch runners. There were eight runners per regiment in what was a highly dangerous and important job: taking orders from Regimental HQ to the front line commanders, and returning with replies and reports. The average person today has no idea how important this was (and is). Under the constant shelling inherent in trench warfare, wire communications were unreliable at best and often unavailable. Radio was in its infancy and seldom used on the front (tubes do not hold up well to shelling and machine-gun fire, and the average radio at the time required several horses or mules to carry the equipment. Rather impractical in a trench). The only way to communicate was directly. Dispatch runners, therefore, often found themselves advancing under enemy fire while their comrades were not.

“On Hitler’s first run during the Battle of Messines, six miles southwest of Ypres, three runners were killed and one wounded of the eight on staff. On the second day, the regimental commander was wounded near Hitler and Schmidt; under heavy fire, Hitler and Westenkirchner carried their wounded commander to an aid station. Hitler was promoted to corporal for bravery. “

Ibid

For this action, Hitler received the Iron Cross, 2nd class. He was nominated for the 1st Class of this award, but due to the bureaucracy of how awards are apportioned, he received former. He did not care. To be recognized and awarded by his beloved Fatherland was enough. Indeed, “Whenever anyone asked where he came from Hitler would reply that his home was the 16th Regiment – not Austria – and after the war he would live in Munich.”

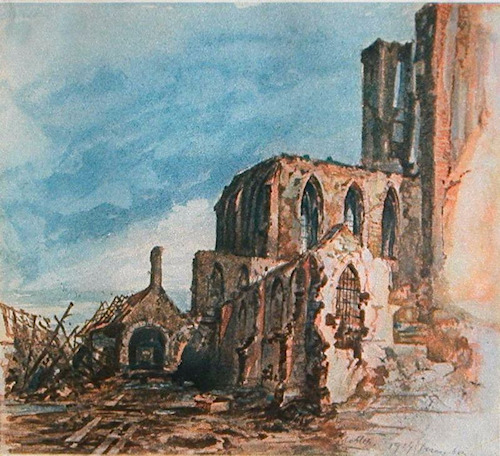

During lulls in his duties, Hitler would often read, paint, or sketch. He had a sense of humor: once a fellow shot a rabbit to take on leave, but a comrade swapped out a brick for the rabbit in the parcel the man carried home. “Hitler sent the victim of the prank a postcard – with two sketches, one of the soldier unwrapping the brick back home and the other of his friends at the front eating the rabbit.” (Source: Adolf Hitler, John Toland)

In short order, Hitler became indispensable to regimental headquarters. “We found out very soon,” recalled Lt. Wiedemann, “which messengers we could rely on the most.” Wiedemann, in 1935, became Hitler’s adjutant and although later dismissed for disagreeing with Hitler’s foreign policy, went on to say that Hitler’s memory of his war experiences was excellent. “I never really caught him lying or exaggerating when he told of his recollections.” [Ibid].

In 1916, Hitler’s regiment moved south to take part in the battle of the Somme. Throughout the battle, Hitler moved back and forth through watery shell holes and ditches, carrying on while others collapsed from exhaustion. Finally, in October, his luck ran out and he was hit, along with other messengers, by a shell exploding as they slept in a sitting position in a narrow tunnel near regimental headquarters. Wounded in the thigh, others might argue that he had the “golden ticket” off the front lines. Not Hitler. He argued with his Lieutenant, saying “It’s not so bad” and pleading to stay with him and the Regiment. But he was evacuated to a field hospital all the same. From there he went to a hospital outside Berlin. Eventually he was transferred to a replacement battalion in Munich.

As would be expected of any front-line soldier having to rub shoulders with civilians in the rear, Hitler became disgusted with goings-on in city (and noted the number of Jewish shop keepers still open for business). He wrote to his Lieutenant and by March was back with the 16th Regiment.

That summer the regiment returned to its first battlefield, participating in Third Ypres. After continuous fighting, the shattered 16th Regiment was finally relieved in August and sent to Alsace for rest. In October, Hitler took (or was forced to take) an 18-day furlough (his first of the war). Although the rest of the year passed quietly for the Regiment, the winter of 1917/18 was a tough one. Rations were low and the men were forced to eat cats and dogs. Hitler preferred cat, as he very much loved dogs.

As Winter ended and Spring began, the Regiment again found itself in the thick of things, taking part in all phases of the Ludendorff offensives: again on the Somme, the Aisne, and the Marne. It was on one of his trips in the vanguard that Hitler, spotting a French helmet “crept forward and saw four poilus [French infantrymen]. Hitler pulled out his pistol – messengers had turned in rifles for side arms by then – and began shouting orders in German as though he had a company of soldiers. He delivered his four prisoners to Colonel von Tubeuf personally and was commended.” (Toland) Though technically not for this action, but instead for previous instances of valor, on August 4, Hitler was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class.

Of Hitler, Colonel von Tubeuf said, “There was no circumstance or situation that would have prevented him from volunteering for the most difficult, arduous and dangerous tasks and he was always ready to sacrifice life and tranquility for his Fatherland and for others.”

Adolf Hitler, by John Toland

By early September, the 16th Regiment was again digging in around Ypres. On the morning of October 14, Hitler was blinded by gas near the village of Werwick. It was while he lay in hospital recovering from the gas attack that he learned of the war’s end.

This is an abbreviated account, of course. But I hope it serves to give one pause the next time they hear someone disparage Adolf Hitler’s front-line service for Germany in WWI. In addition to both classes of the Iron Cross, his medals included the Military Cross, 3rd Class with Swords; the Regimentsdiplom for outstanding bravery; the Medal for Wounded, and the Service Medal, 3rd Class. He remained a Corporal because a promotion to Sergeant would have forced him to leave the Regiment. This he would not do. As one might say later, his Honor was Loyalty.

Happy Birthday my Führer! Sieg Heil!

2 responses to “A Birthday Remembrance”

An extraordinary post. In my 50 years of research, since college days, I have never seen a more concise and remarkably accurate history of Hitler’s war experience.

That’s very kind. Thank you!